Glioblastoma patient advocate

In August 2023, my younger brother was admitted to the emergency room and diagnosed with an aggressive grade 4 brain cancer, called Glioblastoma.

Learning that he had 14-16 months, I suddenly became a caregiver and supported my mom who is a non-native English speaker and living with low income.

During my journey as his caregiver, there was overwhelming medical and financial information that our family had to process, adjust, and adapt to successfully help my brother in his care. This includes doing my time-consuming research to ask the doctors the right questions about the treatment options, being fastidious in potential medical treatments, asking for referrals for outpatient services, and following through with authorizations and referrals.

Aside from navigating the medical system, we had to prepare ourselves for the new "normal" when my brother was discharged. We transitioned into the home to include his medical equipment around the house, looking to state and county programs for financial support, transportation services for his daily treatment, and supportive services related to his daily care and hygiene.

I’ve learned that I am not alone. A New York Times article estimated 53 million Americans are becoming caregivers spending +20hrs per week taking care of someone who has suddenly become ill. They are the “backbone of long-term” care for patients who have to lose their jobs and take care of someone without financial support.

I have joined my sister's mission and non-profit, Patient Led Foundation, as a Patient Advocate for Glioblastoma, to provide resources and support for those who are in this journey with us.

Her mission is inspired by being a patient, scientist, and entrepreneur who had to navigate the medical system for her diagnosed retinitis pigmentosa in 2010 with no standard of care. Her challenges taught her the power of shared information and knowledge and self-advocating. Patient Led Foundation is building a community of information and resources to support patients and their caregivers in navigating their care.

- Le Nguyen, Patient Advocate for Glioblastoma

Lead us from darkness to light: Navigating the hospital

In the midst of developing my organoids and helping patients navigate their own cure, I had unexpectedly become a cure guide for my brother’s brain cancer. This was devastating for me and most importantly my mother as I can barely fathom the turmoil she’s going through as a mother of four, low-income, and a non-native english speaker. As someone who is both a patient with a rare disease and a cure guide for others, I started reflecting on the common challenges patient’s with rare disease face and made a to-do list for those who are figuring out how to navigate this as well.The challenges we face

Lack of diagnosis/prognosis. There are a few layers of unknown that patient and their caregivers have to navigate. There is still so much we don’t know in medicine and science. As a scientist we may have a therapy that shows some promise but there are gaps in whether it works in patients. Families believe medical professionals know the answer on how to fix or manage the patients condition, let alone sometimes they expect doctors to know the diagnosis. However, the truth is these answers are still educated guesses and very few tests exist out there that can give definitive answers.Lack of time. These unknown still falls onto caregivers who carry that burden of not knowing, waiting for answers, waiting to talk to medical professionals all the while society forces us all to continue to work and pay the bills with barely 2 weeks alloted grievances/bereavement leave. Even if we don’t have the answers, it’s the timeframe of the unsuspected, abrupt notice of medical procedures, updates, and transfers that interferes with the day-to-day and not to mention the emotional turmoil of fighting and begging work to allow us to take that time to adjust.Lack of medical jargon. This is the another language barrier that caregivers face as most of us barely have biology background let alone the medical understanding of what's happening to the patient. But they are tasked with the responsibilty of navigating and understanding the gravity of these decisions they both have to make.Lack of financial support. Things until a patient and their caregivers having to navigate this. Having to navigate the medical system to get answers, the financial burden, and family dynamics while not having the knowledge or vernacular to speak to it let alone the emotional trauma you’re dealing within yourself. I had to chase down social workers to find local financial support and resources to help pay for something as simple as parking for my mother who came in everyday.Lack of emotional support. These seems like the last thing to provide but it should be one of the first and a calm demmeanor can go a long way in the medical profession. This can also be provided through social workers who are trained to provide local resources to mental health professionals as well. Persistent stress is emminent in medical cases that take a long time. The marathon of chasing doctors, nurses, social workers, and case managers takes a lot of time and a toll on your mental health. Burnout becomes common and the guilt of not being able to provide emotional support for the patient is eating away your hopes and strength.Teetering between grief and hope. There are days when you look at your child or family members suffer and grief seems to swallow you into this dark, infinite space of sadness and emptiness. You lose sense of time and relevance of the world around you and you can barely “function” as a adult let alone a normal human being. In those times of grief, sometimes doing the motion of making breakfast or walking around seems like an empty meaningless thing your body does without intention. Those are the days when you need to establish a process to help ground your mind to your body. I find swimming is my grounding where I can do something aimlessly but it helps my mind remember that I still need to keep this body alive and healthy and are limited by the air you breath. That grounding will help me snap back into my body and engage with my bodily needs again. Grieving the grief helps make space for joy, happiness, and hope. It’s part of the everyday process and if it gets trapped and not expressed, grief becomes depression and potentially prolonging your ability to support yourself and others who need you.

What to do in the hospital

Nurses are amazing human beings. They take care of the patient and most of them are in the dark of the next steps. So please be kind to them. Offer them meals as they are taking 12 hour shifts to ensure the best care while you're not around.Doctors are the gate keepers to diagnosis and prognosis. They are the ones who interpret the data and help provide options for the patient. It's important to know which type of doctor to talk to since each doctor can only chime in on their speciality. Have the nurse help you get the attention of your specific medical doctor to talk about the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment options.Case managers help you figure out insurances and get the needs/care the patient needs. Make sure you have an assigned case manager. They are typically nurses who know about the medical condition and can help navigate your insurance and what services are covered and local clinics and facilities that will help the patient.Social workers will connect you to financial resources that the hospital or clinic provides. They should connect you to local disability resources provided the local, state, or federal government. Ask for long-term parking permits and vouchers to subsidize your hospital stay. You might consider searching for financial support for the patient and potentially enroll them into unemployment and/or disability insurance.Don’t forget to find mental health providers that can assist you as the caregiver. In the end, you are a project manager for the patient and helping the navigate this while they can’t is helpful.Occupational, speech, and physical therapist are good people to meet. This means the person you’re caring for are on the mends. Occupational therapy and speech therapist help the patient learn how to do functional things like stand up and learn how to walk while speech can help with things from speech to swallowing.Who is the beneficiary? The beneficiary takes care of and/or manages the patient’s assets. Make sure to follow-up with bank accounts and credit cards.

My brother is going through his 2nd resection today, so I hope I can provide an update on the to-do list on how to navigate medical care outside of the hospital. For now, we continue to provide space to grieve and clearance for hope.

Love Light

From One to Many

Another poetry submission that describes my rare disease and what inspires me. I hope this inspires all of you who are conquering the day-to-day and fighting a good fight.

Poetry submission: A stranger’s perspective on my vision loss experience

I’ve submitted a poetry submission and I’m hoping it will get published to provide a patient’s perspective on losing their vision. I had 30 minutes to write and this is what I felt deep down inside during a time when I was learning how to grow stem cells and it’s been a little over a decade since I’ve cultured cells. I was getting critiqued without compassion and felt defensive because yes I will defend myself. I’ve also had a few people yelling at me about whether I was just “using that cane as a prop” because I was able to see when it was fully lit versus when it was dimly lit.

What helps me the most during those times is to understand that people are projecting their frustrations onto me. So it’s not me who’s the problem, but it’s their inability to love and find compassion within themselves. Because so many of us have gone unloved for so long that we have forgotten to do it.

Phase 1: my stem cells

For the past 6 months, I’ve been training myself to make stem cells. Of course, what does making stem cells entail? Some may have learned early on that your body stops producing stem cells except in your hippocampus and olfactory bulbs. My friends and family would ask why are you doing this? Or more importantly, when will you stop going to school? Well, I hope this post will answer all of your inquiries.

First I want to provide some background into stem cells and give attribution to the amazing feat that deduced a complex process of literally Benjamin Button-ing adult cells back to their nascent stem cell state. Around the mid-2000s, scientists figured out a way to take adult cells such as fibroblasts and later peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and reprogrammed them into induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSC). After many passes through different combinations of transcription factors and oncogene, they deduced the necessary genes to reprogram human cells down to these main activators: KOS (polycistronic Klf4-Oct3/4-Sox2), Myc, Klf4 (because one is not enough) (see this amazing review of the history of stem cell historical discoveries Omole and Fakoya, 2018).

From what I hear, it’s one of the hardest cell culture protocols. So why am I going down this path of creating my own stem cells? Well because my masochistic tendencies love to explore the hardest but shortest path of modeling my own disease.

“Why couldn’t you just hire someone to do this for you?”

Well, science and labs are in short supply and even if I paid someone to make my stem cells — which you can — I am still short of modeling my rare inherited retinal disease. Stem cells are only a precursor or the first step to making a disease model after a patient’s specific gene mutation. The next step is to take stem cells and study the cells that best represent the disease. In my case, a retinal cell is the best way to study my retinal disease.

“Why do you need to study retinal cells from humans? Couldn’t you study this in animals?”

I wish I had the luxury to model my disease on animals. Here’s the catch, EYS does not exist in rodents. I repeat EYS gene is nowhere to be found in the rodent gene and this includes mice, rats, squirrels, and tree shrews (we’ve looked). But we have studied them in our favorite fish and invertebrate animal model, zebrafish and drosophila. Although we can study it, the EYS gene between humans and zebrafish shares about 33% similarity. This makes it hard to map the mutations that cause my disease from humans to fish and vice versa. Second, if I were to find a treatment using gene therapy and I had used a fish to model my disease, then I would have to design the therapy for the fish first and then I would have to go back and re-engineer that therapy to my gene. So given my conundrum, I needed to find a lab in the Bay Area that would study retinal diseases using patient-derived cells. In fact, I found professor Deepak Lamba (lab link) who models retinal diseases by making mini-retina clusters in a petri dish called retinal organoids. He works in reconstructing the retina morphologies from patient-derived stem cells so we have a better understanding of the mechanism behind the disease. If you wanted to know how I ended up in Deepak’s lab, check out this post here.

So I started my first cell culture in a little over a decade by grabbing a frozen aliquot of PBMCs (peripheral blood mononuclear cells) that have been collected from my blood draw back in June (boy, do I look like a freshman grad student, innocent and naive).

Back in June, I pose with my my blood draw and getting ready to get it processed in the lab.

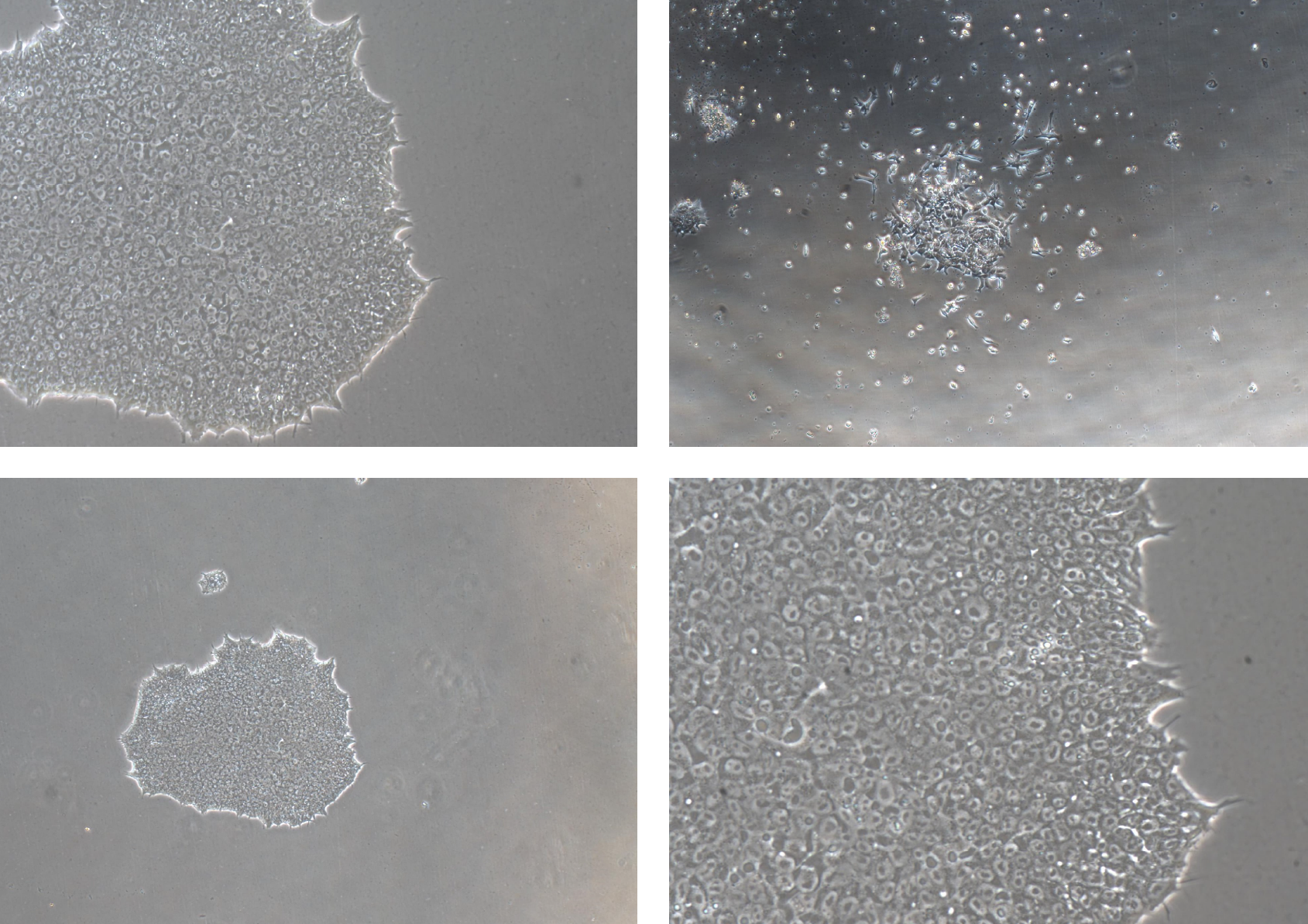

I’ve attempted 2 times to reprogram the PBMC to IPSC and I’ve always stopped short 35 days after reprogramming to find either no colonies or small colonies that went nowhere (see the image). I’m telling you it’s very sad. They just refused to grow. What gives?

Day 34 and colonies were no more 16 cells.

Third time’s a charm, right? Well, the charm came from reprogramming fresh blood right after finishing up running some tests for ProEYS Natural History Clinical Trial that I am in (see link to learn more). And yes, it made a HUGE difference. Because in less than 13 days, I got colonies so big that I started picking them early. So far every 4-6 days, I kept picking colonies and started my passages. Today I am on passage 3 of taking undifferentiated IPSC colonies and culturing them so that we only have undifferentiated IPSC colonies. This guarantees that you have cells that are most likely stem cells and not cells that have been differentiated into something.

Stem cells packed into a single colony compared to very spaced out differentiated (non-stem cells). Top left: 10x magnification of colonies. Bottom left: 4x magnification to see entire colony. Bottom right: 20x magnification to see packed cells. Top right: non-stem cells not packed densely into a colony.

Now that I am finishing up the first phase, the second phase of making mini-retinas (retinal organoids) will start as soon as the first of February. This second phase is long and arduous and requires the forethought of making enough organoids that can survive more than 150 days, which is when photoreceptors start to appear. It is then that we hypothesize that EYS protein will express near the base of the outer segment as seen below in macaque retinas.

EYS shown in green is expressed at the base of the outer segment of both rod and cone photoreceptors. You can see the higher expression of EYS in the outer segment of blue cone receptors, which is co-stained with blue opsin (Yu et al., 2016).

Then we beg to ask, what does EYS do that is so important in the retina? What do the mutations do to my retina that renders me to lose my vision in my 30s but somewhat perfectly intact until my adult life? Will I even see any differences in the mini-retinas between my mutations vs. healthy ones? I hope to answer some of these questions in Phase 2.

If I could get any help in this journey, it is to connect to experts and collaborators who are interested in the following unknowns:

The preclinical requirements of getting treatments prepared for clinical trials. How does an N-of-1 (1-to-N) toxicology screen look like for someone who is screening treatments on retinal organoids? Is organoid or cell survival enough?

Are there any therapies worth testing that can preserve and protect existing photoreceptors? It could be anything from NAC (n-acetyl-cysteine) to Antabuse and metformin.

What are some worthy experiments/questions besides protein/transcript expression in these organoids? Harder questions like how to search for other protein-protein binding interactions? How to target for each of the four different isoforms?

Until then, spread the word, the awareness of (1) rare diseases and how most of them are left unstudied, (2) those who are fortunate like me can find funding to research my own rare disease, and (3) there are pathways being paved now as I continue to help patients through Perlara. Never give up hope.