Chapter 1. Diagnosis

How can we improve the patient experience and journey? Well before I answer that question, I wanted to share my experience and maybe some of this resonates with you. This is the breakdown of how this all started:

Geminid Meteor Shower in 1998

I was out with my friends in high school to view the meteor shower of the year. As a nerd, I had gotten special permission to lounge out on the rooftop of music class to view the meteor shower. We set ourselves up with EANABS and our favorite snacks and abruptly my friends turned, gasped, and marveled at the reverse, firework spectacle above us. It was gorgeous so they say as I doubted whether my friends were teasing me. I felt the explosion of confusion and pain flood inside me as the surrounding wonderment slowly drowned out. It was clear what was happening because I honestly did not know what did happen. But I walked home that night silent and alone among my good friends.

Since then, I nagged my optometrist every year about that night without the vernacular or comprehension of what happened. I did my best to explain my observations, “I just couldn’t see the stars.” And for 10 years, I was told that I had to adjust to the darkness a little longer. The advice made sense except after a long hour of sitting in the dark, my eyes never adjusted and my center of gravity felt disoriented instead. Or maybe it was my lenses was not corrected enough, so we again changed my prescription, and still 20/20 vision. In an era of AOL, I relied heavily on my optometrist (remember AIM?). So searching for “special eye doctors” and content was accessible as encyclopedia books. You heard me right, there was a time before Wikipedia because the internet was barely learning how to walk. While navigating the infant stages of Facebook and MySpace in college, I became the reverse vampire exploring campus life between the hours of operation 9-5 pm, and having an exclusive social life no later than dusk.

Even then I had tried to party which ended up being a flower wall because of exquisite dim lighting that was every bar and every party scene go to the mood setter. It was a buzzkill as I realize my preferred or vision-friendly settings are cafes and boba places.

These “life adjustments” were just a short preamble to the modifications I endured when I begin my journey into grad school.

Diagnosis

Orientation week at Stanford was a rush and full of excitement. I had just spent two weeks prior partying with my friends and family at the NIH and SoCal, so I was ready to be a serious graduate student and learn the ways of academia. After getting myself acquainted with the social structure at Rains, I had one more thing to check off my list which was setting myself up at the Vaden Health Center. It was painted with Stanford's iconic cardinal colors and it felt more like a tech office than a health center with the front desk dressed with educational pamphlets on self-care. I remember my first visit to my optometrist there and after so many years of saying the same thing, I figured I just note that I can’t see stars. I remember his uncanny response, “Oh, we need to refer you to an ophthalmologist.” I have never heard of ophthalmologists and I was both excited and scared. I was for the first time being referred to a doctor that knows something about me not seeing stars. I felt taken care of.

After several hours of retinal scans and visual field testing, this was the rub: I had retinitis pigmentosa and there was nothing I can do about it. In that hot moment, the adrenaline of joyful validation completely electrifies my muscles while instantly a dark shadow of depression sunk that validation into the deep abyss. There is not much that has been known about it. I asked do we know what genes are involved and can I get sequenced? My ophthalmologist replied, I think there are some guys in Oregon who are doing that but nothing available to patients right now. There are places like the Lighthouse that can set you up for a vision cane. You don’t need it now but the next step is for you to measure your progress on an annual basis. There is this one study that demonstrated that 10,000 IU of Vitamin A slows down the progression but it’s not statistically significant.

A bombardment of questions pierced through my interrogation: do I need a vision cane? I just drove over here and I have a car, should I stop thinking about driving? So 10,0000 IU of Vitamin A to slow down the progression of my disease? I will take what I can get. Anything to buy me some time to think about this. Am I going to be blind tomorrow?

Leaving the clinic more confused than validated, I began to reconsider my clear career path of becoming a professor. Would becoming a professor help me further the work that needed to be done. I couldn’t even get the care I needed and let alone find the support and communities. I did consider it. I went to all the talks and my first one was from Dr. Daniel Palankar he developed Argus, a cyborg CCD camera implant onto the optical nerve that replaces your complete loss of vision. There was also Dr. Stephen Hicks who was one of the first to implement google glasses technology and augmented and enhanced. It was the closest thing to helping those who are still suffering from loss of vision and still have some vision left and amplify their existing vision with the help of some augmented glasses.

Before I knew it, I had already shifted course. I began switching my life pursuit from a career mentality to developing a cure mentality. How do I begin to help myself and those who suffer from the same infliction? Where do I begin? Or do I just accept my fate and learn to adapt? How I answered these questions defines the life ahead and most importantly transforms it into the mission I’m working on today.

NIH grant approved to develop my retinal organoids

Monday, April 26th, 2022, I received a 10 pm email from Deepak Lamba (link to lab), a professor at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) whom I’ve been corresponding about his work on stem cell technology and development of retinal organoids. The email says, “I just saw a notice dated tomorrow (4/27) that your supplement got approved. Congratulations and welcome to the lab!”. My eyes widen and immediately I jumped out of my chair before it hit the bookshelf, I got to Matt and said, “I got the grant!”. A few moments later, my doctor, Jacque Duncan — who is still running the Natural History Clinical Trial, introduced me to FFB, and the low vision community — has emailed me to congratulate the approval of the grant. It was a moment of disbelief, joy, and warmth from the community of people who have supported my journey thus far and further.

What is this grant and what does this mean for me?

I had just received approval for a Re-Entry Grant funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH), which funds individuals to return to academia after leaving between 6 months and 8 years (link). For those interested, you need a PI to sponsor you and submit the grant application which is comprised of (1) biosketch, (2) grant proposal, and (3) personal statement. Your PI needs to submit a budget detailing the next 2 years of the work and more supplementary information. Although many saw this as a way to develop their skillsets, for me, it meant I can research my specific variant and understand how EYS is causing retinitis pigmentosa. It meant that if we can develop these retinal organoids, which are mini-retinas grown in Petri dishes, we can model one of the first late-onset retinal diseases and observe morphological differences. Furthermore, we can develop and experiment with several therapeutic approaches, such as gene editing directly on my retinal organoids.

What is my ultimate goal?

My biggest hope is that I can transfer this knowledge, this self-cure guide experience to others suffering from rare diseases. It can be this particular path or similar paths that lead to the endpoints needed to derisk the therapy and demonstrate efficacy early in the preclinical process. If we can make these observations early, we increase the chances of success later and make collecting data less expensive for families and foundations. These points alone are priceless for the families and communities inflicted by rare diseases and who rarely get an opportunity to find a researcher working on their disease. Can we improve modeling pathology systems and get more insight into therapeutic efficiency, drug delivery success rate, and toxicology? Each of these insights would easily cost $1M and if we plan to find a treatment plan for every 7000 rare diseases, then the infrastructure and the cost need to change dramatically. Here’s one vision of creating a network of mini-CROs to help build this affordable infrastructure (link) and another is to create a research institution like Broad that dedicates a lot of resources to studying rare diseases (link). As we build these infrastructures for the N-of-1 or N-of-few, we see the entire clinical pathway benefits and we see a more robust system that can take on more diseases that don’t fit the typical medical cookie-cutter mold. We are able to accommodate the rest of the medical cases that are one to two standard deviations and EVEN outliers.

We cure via decentralized micro-labs

Gene Fixer’s clubhouse conversation focused on building a decentralized micro-lab ecosystem that enables research for rare diseases to collect preliminary data and derisk the opportunity cost of unknown diseases. This is the only way we can scale research for over 7000 rare diseases just in the U.S. (NIH NORD, 2019). Here’s how dire the situation is:

29,000 diagnostic and medical labs in 2022 (IBSworld, 2021)

The NIH funded grants breakdown based on the type of disease in 2020 (NIH, 2020)

$17.6B went into clinical research (preclinical and clinical trials)

$10B went into genetics research

$10B went into neuroscience research

$8B went into infectious diseases

$7.0B went into cancer

$5.9B went into rare diseases (< 0.002% of NIH funding)

And the funding mechanism is dire because it is hard to get funding for a rare disease when it does not affect many people and therefore the impact feels small. Most grants will fund $5-$20M for 5 years and in the best-case scenario, we might have 10 labs working on one rare disease.

We need a better plan, a better infrastructure, a better funding mechanism, a better business model to build more resources to do the research for the 30 million individuals affected by a rare disease. Some of the ideas around creating micro-labs or micro-CROs also included digital infrastructure to manage the data and data sharing.

Hackathons are a great way to get a lot of people to solve a problem. How about we take university classrooms and convert a biology course studying protein trafficking and train them to solve protein trafficking diseases? What if these classrooms became dozens of hackathons throughout the U.S.? And what a better way to learn about biology is by solving the problems of biology. These universities don’t have to be the Harvards and Stanfords, but liberal arts colleges that have the infrastructure to do cell culture, imaging, microbiology. We can enable so many more people to the conversation and truly decentralize the efforts funded by the NIH.

To hear a clip of the Gene Fixers on this, click here. If you would like to collaborate please reach out via [email protected] or through Contact Us.

natural history clinical trial for eys

I wanted to share my personal experience of losing my vision slowly through the lens of a patient scientist. I got the opportunity to be part of a four-year Natural History Study for my gene-specific retinal disease called ProEYS. This data collection effort funded by the Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB) is to better understand the disease progression for patients with variants in the EYS gene. Before this, I was fortunate to learn about a free genetic test panel that was conducted by Blueprint Genetics in collaboration with FFB and once I got the gene and the mutations in that gene, I was lucky to meet a genetic counselor to help enroll me into the study, which started in 2021. Lucky for me I qualified for the study but before then I had no idea. When I was diagnosed in 2010, gene sequencing wasn’t as readily available to patients and consumers as it is now.

So what does a study like this mean? Do I have a treatment already? No. It is the first step in the right direction. Although retinitis pigmentosa (RP) has the same underlying mechanism, which is the degradation of rod photoreceptors, not all genes related to RP have the same degradation. Because there are at least 80 genes related to this, there are at least 80 different ways and not including individuals who may have crossover in these expressions. Some are more severe than others and some may live with some functional vision well into their 80s. A lot is still unknown. So these studies are helpful.

So far, my visits have been once a year, which entails at least 4 hours of OCT, VF, and additional measurements that are related to the study itself. If they have data that is specific to the research, they might be exploring new ways to measure the disease, in which case, you’re not privy to that data. So keep that in mind when participating in these natural history studies. So on top of these visits, I still visit my doctor at the Casey Eye Institute in OHSU because I get all the raw data from my measurements. I HIGHLY recommend it.

So next steps, I’m being patient and waiting to continue to collect the data, but I hope my next efforts / journey related to potentially working on creating my own retinal organoids update will bare more results. Until then, self-advocate my rare disease crusaders!

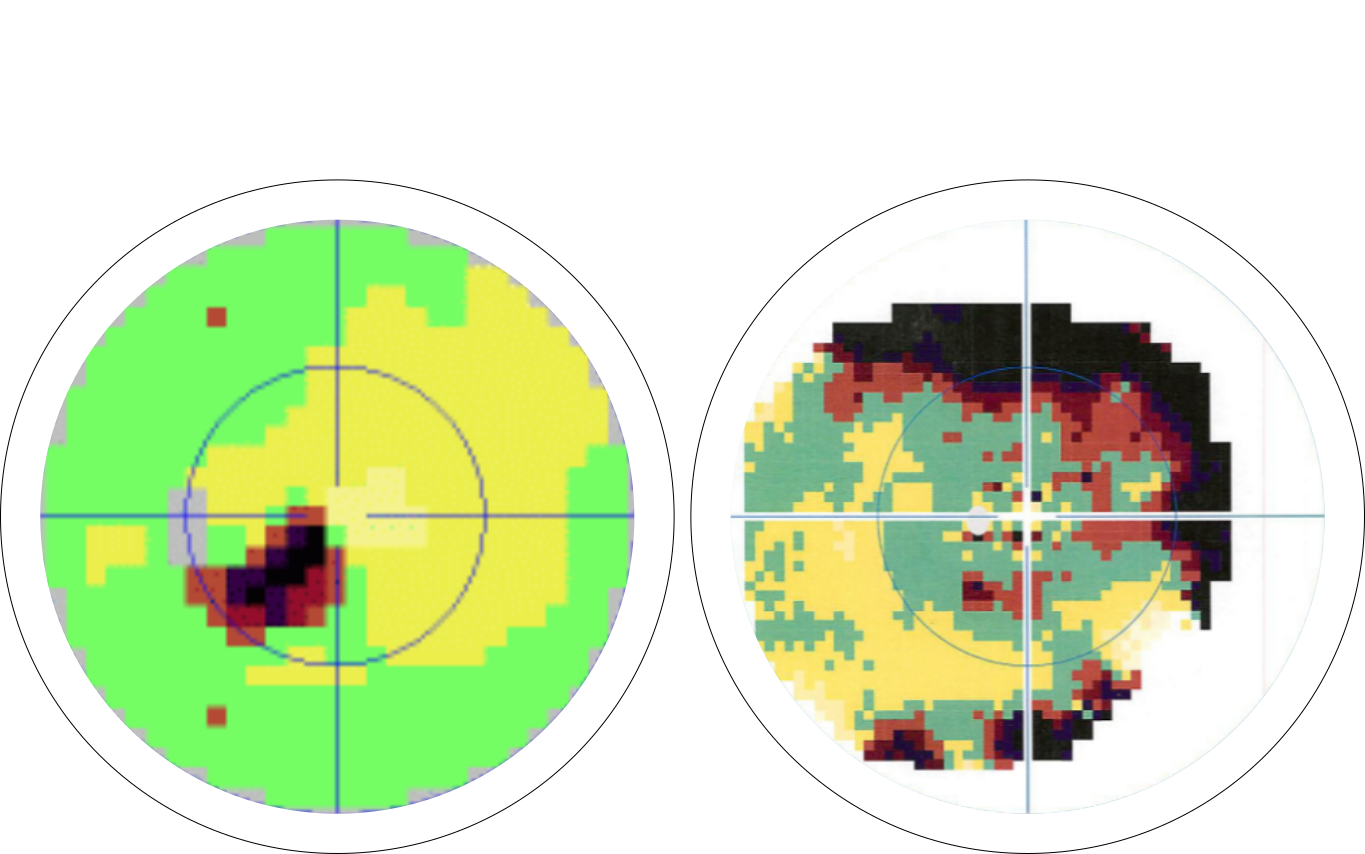

This is a visual field captured using Octopus and it’s measuring visual sensitivity of a patient’s visual field. Green indicates positive response to stimuli and dark reddish color indicates negative response to stimuli.

patient perspective for Rare disease day panel

I’ll be sharing my personal journey with retinitis pigmentosa on Rare Disease Day on Thurs 2/24 9am EST. Please register below and listen in on the latest treatments, patient advocacy, and lifestyle resources.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Retrospection: it was fun to be on the panel and nerve recking. I was the only one providing a patient perspective on a very research-driven panel. I had the opportunity to share my perspective and why building cures in a customer/patient-centric manner can only help your innovation. As someone who has built B2C products, often companies forget the patients and think they can cure the disease. But the success also lies in patient compliance and acceptance of the treatment as well the cost. In sharing the patient perspective, I hope to share not just patient insights but help engineer and design therapies that work from the business model side.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Innovation in Rare Disease: Making Progress with Cell & Gene Therapies

https://www.syneoshealth.com/events/rare-disease-day-2021